We are living in an era of change, and one fundamental human right being addressed now is the injustice and imbalance of how certain groups are perceived in society and how it affects their advancement in life. At the heart of this change is progress in women’s rights globally and the desire to create a more equal society.

Embracing differences while ensuring equality is often a fine line, and when it comes to the sexes, semantics often underpin this. You frequently hear it said that the language men and women use is different, and that this has far reaching implications in everything from how people understand each other to how they progress in their careers.

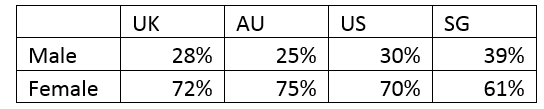

With this in mind, we decided to conduct a study across the US, UK, Australia and Singapore to explore if there are differences in the way people describe themselves, and also the differences in how they perceive others to describe them. The purpose was to explore both cultural and gender differences in the semantics and identify if language really is something that holds women back from the rights they deserve.

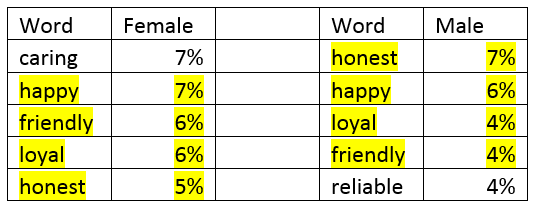

The study was fairly simple in principle; the crux was to ask people how they would describe themselves in various situations. The core question being ‘If you had to describe yourself in three words what would they be?’ Looking at the word choices, we found that four of the top five most used words for both genders were in fact the same: happy, honest, loyal and friendly.

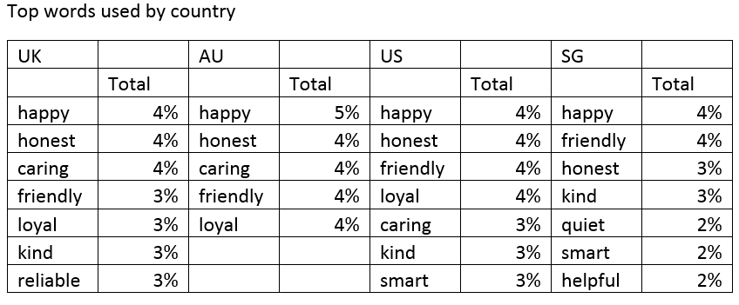

However, breaking this down by each country, we saw some stark differences.

Here you can see the exact same order for the UK and Australia respondents, but Australia respondents had a greater use of five in particular. In the US, ‘smart’ entered the lexicon more than the other markets, while ‘quiet’ was a key word in Singapore, indicating some cultural nuances at play in what people value and perceive.

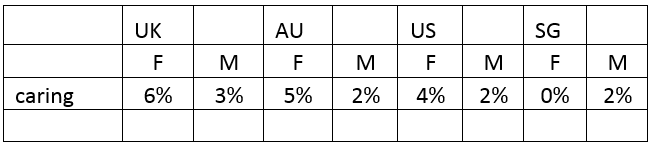

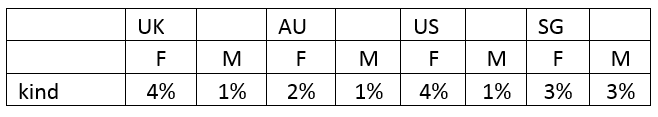

It became really interesting when we looked at the differences in gender usage of the words 'caring', 'kind' and 'reliable'.

Looking at the use of the word ‘caring’, we saw differences between male and female usage in most of the markets; the same being true of the word ‘kind’. There were some markets where this was less dramatic, or actually not used at all (i.e. Singapore). Clearly we see an indication of a societal value that is being gendered.

Looking at the use of the word ‘caring’, we saw differences between male and female usage in most of the markets; the same being true of the word ‘kind’. There were some markets where this was less dramatic, or actually not used at all (i.e. Singapore). Clearly we see an indication of a societal value that is being gendered.

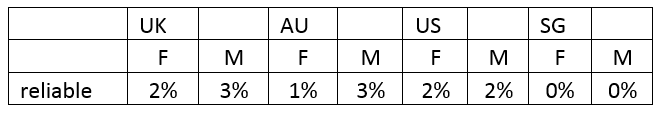

Men instead focused on terms like ‘reliable’, which saw greater use by males in Australia and the UK, but it was equal for US and not used at all in Singapore. This again suggested that gendered roles and values are reflected in how people wish to be portrayed.

Men instead focused on terms like ‘reliable’, which saw greater use by males in Australia and the UK, but it was equal for US and not used at all in Singapore. This again suggested that gendered roles and values are reflected in how people wish to be portrayed.

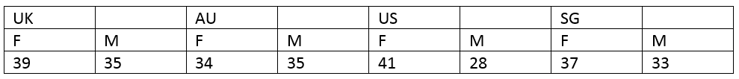

The findings showed that women used a broader range of descriptive words in their responses- 53 for female respondents and 48 for male respondents.

Both the greatest and least number of words used were in the US, with females at 41 words and males at only 28. One can speculate on the implications of this, however it is clear that certain groups displayed more diversity in their descriptions.

The second part of the study was to explore how people perceive language when gender applied to others. We presented respondents with gendered profiles of various individuals where we gave a limited amount of information, such as their age or marital status. Respondents were then told that one of the individuals presented had used certain words to describe themselves or others. Respondents had to choose who they thought had done so.

The purpose was to see how language is perceived as gendered and how various personal aspects interplay with how far perceptions are ingrained.

The results were in some instances quite bleak. For instance, when asked who would describe themselves as “ambitious, smart and hardworking”, we found that a greater percentage of respondents depicted this as something a male, would say. In fact, 2/3 of respondents identified this with a male, with the highest in Australia and Singapore at 67% but on a similar level were UK and US at 62%.

However, when we changed just one of these words ‘hardworking’ to ‘warm’ and asked who would describe themselves as “ambitious, smart and warm” this almost directly flipped to our female. US respondents felt most strongly about this at 66%, followed by the UK and Australia (63%). Singapore was closer with 59% seeing this as something a female would say. Making it clear that ‘hardworking’ versus ‘warm’ is a bias that interplays in people’s perceptions of the genders.

We extended this method to see who would describe others in particular way. In one instance we chose a professional environment and asked who they thought had described their boss in a certain way. When it came to “manipulative, mean and bossy” it was the 3/4’s of the UK who found the female most likely to say this, at 75%. This was also common for US (71%) and Australia (69%). Singapore again was more balanced between the two with 52% for the female and 48% for Male. But then we flipped the age of the male and female and this changed the Singaporean view dramatically. Here 79% of Singaporean respondents saw 45 year old Julia most likely to say their boss was manipulative, mean and bossy. The other countries were less impacted by this change, Australia rising to 76%, UK down by 3% (72%) and the US dropping to 67%. We then evened things out on the age and made both John and Julia the same age, 45.

Here it became clear that gender was the defining factor in perceptions over who would use these words about their boss. While maturity might have a role, the impact of gender was bigger. Three fourths of Australians felt this would be the words of Julia and similar proportions were clear in UK and US. Singapore still had a lesser gap between the genders here.

Research needs to be catalogued to explore if such perceptions bear any relation to facts. Regardless, it is clear that when it comes to some language, unfair biases are at play. Words like ‘manipulative’ are viewed with a gendered lens that colours perceptions and could be seriously harming Women’s ability to be viewed equally.

This study aims to remind us of the importance in embracing differences and seeking to better understand these nuances to get more from the data we use to know consumers. Taking on board this information but without discrimination or judgement is imperative, both in the delivery of insights and in all that we do as one united front.

*IWD Verbatim Study, 27/02/18- 02/03/18, UK, AU, US, SG MYS and GTM Panels, N=2284